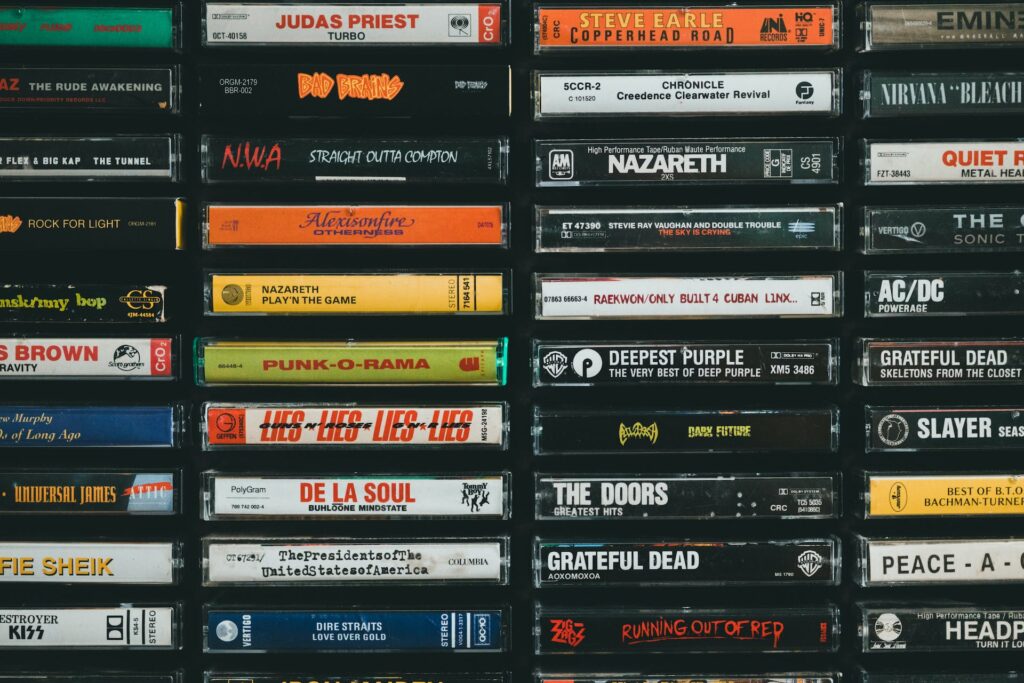

Photo by Jonathan Cooper

Unidisc musique inc. (“Unidisc”) is a company that sells music records. In the normal course of its business, it purchases master tapes of recordings of music (“master records”) in order to make copies of good quality for resale. For the four taxation years under appeal (2010 to 2013), Unidisc categorized the tapes it purchased as tangible depreciable property under Class 8(j) of Schedule B of the Regulation Respecting the Taxation Act, which provided for an annual depreciation rate of 20% for the years in question.

Revenu Quebec disallowed the depreciation at the rate of 20% as claimed by Unidisc on the basis that while the tapes were tangible property, the rights associated with those tapes were intangible property. The tapes being worthless without the rights, Revenu Quebec allocated all the purchase price to the rights, for which the depreciation rate could not exceed 7%.

The Court of Quebec agreed with Unidisc and allowed its appeal. Having found that the quality of the sound was the sole criterion upon which Unidisc relied in purchasing the tapes, it concluded that what Unidisc acquired were tangible property under Class 8(j) of Schedule B of the Regulation Respecting the Taxation Act.

Revenu Quebec appealed to the Quebec Court of Appeal and succeeded.

Unidisc characterized the tapes on its financial statements as intangible property. Revenu Quebec argued that the Court of Quebec made an error of law by failing to view this as an admission. The Quebec Court of Appeal disagreed. How the tapes were qualified for financial statement purposes was a matter of legal characterization rather than an acknowledgement of a fact, i.e. admission. Being a question of legal characterization, Unidisc and the Court of Quebec were not bound by the financial statements.

However, setting aside the issue of whether or not there was an admission and looking at the substance of the matter, the Quebec Court of Appeal agreed with Revenu Quebec that what Unidisc purchased were more than physical tapes. Unidisc purchased “the tapes together with the right to make and sell copies thereof, subject to the right of the composers and publishers of the music and songs recorded on such tapes”.[1]

The Court of Quebec reasoned that since the copyright in the music was not purchased, then only the tapes were purchased. The Quebec Court of Appeal disagreed. Even if Unidisc did not purchase the rights to the music, it purchased the rights to the sound recording, which is a right and therefore an intangible property. Thus, the Court of Quebec erred in characterizing the purchased properties as only tangible. Having concluded that the master records were both tangible and intangible property, the Quebec Court of Appeal turned to the issue of allocation. Unidisc having taken an all or nothing approach, it presented no evidence as to a possible allocation of value between the tangible and intangible property. This led to its downfall:[2]

Although the physical master tapes would have some value apart from the associated bundle of rights, perhaps even considerable worth, there is no evidence upon which to base an allocation between the tangible and intangible aspects of the purchased assets.

Assessments are presumed to be valid, such that the taxpayer has the burden to demonstrate that the assessment is incorrect. This burden must be met by precise and probable proof. Respondent [Unidisc] presented no proof whatsoever. As such, and given the judge’s error in setting aside the assessments, the allocation of all the value of the tapes [by Revenu Quebec] to intangible property should stand.

The way property is categorized for accounting purposes on a financial statement is not determinative of its characterization for tax purposes. However, from a practical standpoint, it can raise red flags. For tax purposes, “property” is broadly defined. As such, when a taxpayer acquires something, he may view it as one property, one “thing”. That may not be true because he may have acquired more than one property, a tangible asset and certain rights that come with that asset. It then becomes a question of valuation and how much to allocate to each “property”. Going all in with a principal argument brings the risk of being left with nothing in the alternative, such as in this case.

[1] Para. 24.

[2] Paras. 34 and 35.