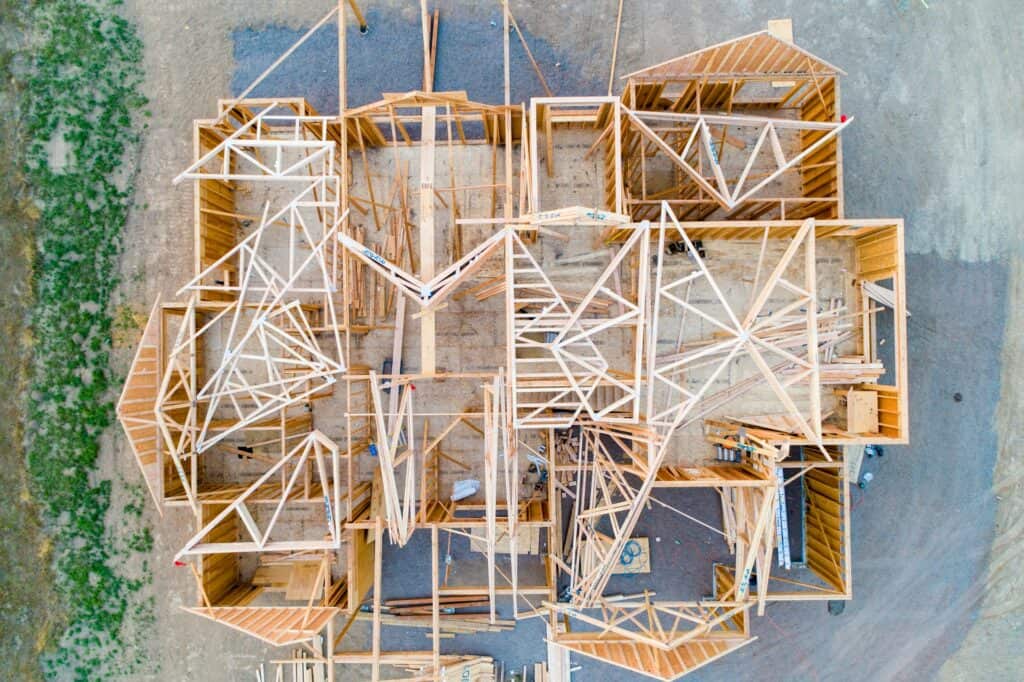

Photo by Avel Chuklanov on Unsplash

In a recent decision of the Tax Court of Canada (“TCC”), the Court dismissed the taxpayer’s appeal of a GST assessment for uncollected GST on the sale of a new house.

In that case, the taxpayer bought a lot. He hired a construction company to build a house. When the house was built, he sold it, but did not collect GST on the sale. The Court laid out the two pathways for the sale to be GST-exempt:

- The sale was made by someone who is not a “builder”, which means that the sale was of a “used residential property”, which does not attract GST.

- The sale was made by an individual who is a builder. At any time after the construction was substantially completed, the house was used primarily as the residence of the individual or someone related to the individual. Further, the house was not used primarily for any other purpose between the time that construction was substantially completed and the house was used as a residence by the individual or relative.

The term “builder” is defined in the Excise Tax Act (“ETA”). Generally, a builder means a person who carries on or engages another person to carry on the construction or substantial renovation of a complex in the course of a business or an “adventure or concern in the nature of trade”. The taxpayer was an account executive and a part-time mortgage broker. He did not build the house in the course of a business. However, the Court found that he did so in the course of an adventure in the nature of trade:

The appellant’s conflation of events and timelines suggests that at the time he acquired the lot to build a house at 56 Rideout, he likely had both the possibility of residing there and selling as dual operating motivations. In other words, the acquisition of the property had the dual character of capital and an adventure in the nature of trade; therefore, the appellant was a builder within the meaning of subsection 123(1).

[Emphasis added.]

Having found that the taxpayer was a builder, the Court then found that the new house was not used primarily as his residence, which defeated any possibility that the sale could be GST-exempt.

The judgment ended with a note that the purchase and sale agreement included a provision that GST was included in the sale price and that the taxpayer may qualify for input tax credits, hinting to some possible relief for the taxpayer.

___________

The taxpayer in this appeal was self-represented. This was probably detrimental to his case because he was not able to establish with clarity his version of the facts. The Court commented that “[d]espite extensive and repeated testimony, the timeline of events surrounding the construction and sale of the property is difficult to follow and pin down with certainty.”[1] The taxpayer further undermined his credibility by contradicting the statements he made during discoveries. Judges at the TCC are tasked with making findings of fact. Those same findings will be relied upon by the appellate courts, unless the appellant can demonstrate that the lower court (TCC) committed a palpable and overriding error. It is therefore critical to set the record straight from the start.

The Court ultimately found that the taxpayer had a “secondary intention” of selling at a profit and qualified the acquisition of the property as having a “dual character of capital and an adventure in the nature of trade”, which meant that he was a “builder” pursuant to the definition under the ETA. Although the case law has laid out a series of factors to consider when determining whether there’s an adventure or concern in the nature of trade, the Court did not explicitly address those factors. The Court also did not elaborate on why it reached the conclusion that the possibility of selling at a profit was an “operating motivation”. This is important because the fact that a taxpayer contemplated the possibility of resale is not, in itself, sufficient to conclude in the existence of an adventure in the nature of trade. Indeed, the prospect of resale at a profit must have been an important consideration in the decision to acquire the property.

The Court reached its conclusion notwithstanding the following findings of fact that, a priori, were beneficial to the taxpayer:

- The taxpayer’s stated intention “to build a house on 56 Rideout where he, his wife, their children, his mother, and his brother could live. Back then, they were expecting a second child and at the time of the hearing, they had three young children. He stated that they could not qualify for a traditional bank mortgage so they obtained three interest-only mortgages from private lenders to finance the construction.”[2]

- The taxpayer had no experience building a house or even “balancing the co-existing possibilities of living in the house or selling it for a profit”.[3]

- The taxpayer’s wife lost her job and based on their total income they could not qualify for a bank mortgage, which forced them to sell the house.[4]

[1] Para. 25.

[2] Para. 13.

[3] Para. 27.

[4] Para. 17.